by Sherrin Griffin VP, Operations, Sidney SeniorCare –

This past July, I lost my Dad. After an 18-month-long odyssey encompassing a hip replacement at 89, severe incontinence, multiple cancer diagnoses and bad falls, countless stints in and out of the hospital, failing mobility, debilitating pain, anxiety and increasing dementia, my poor Dad is finally at peace.

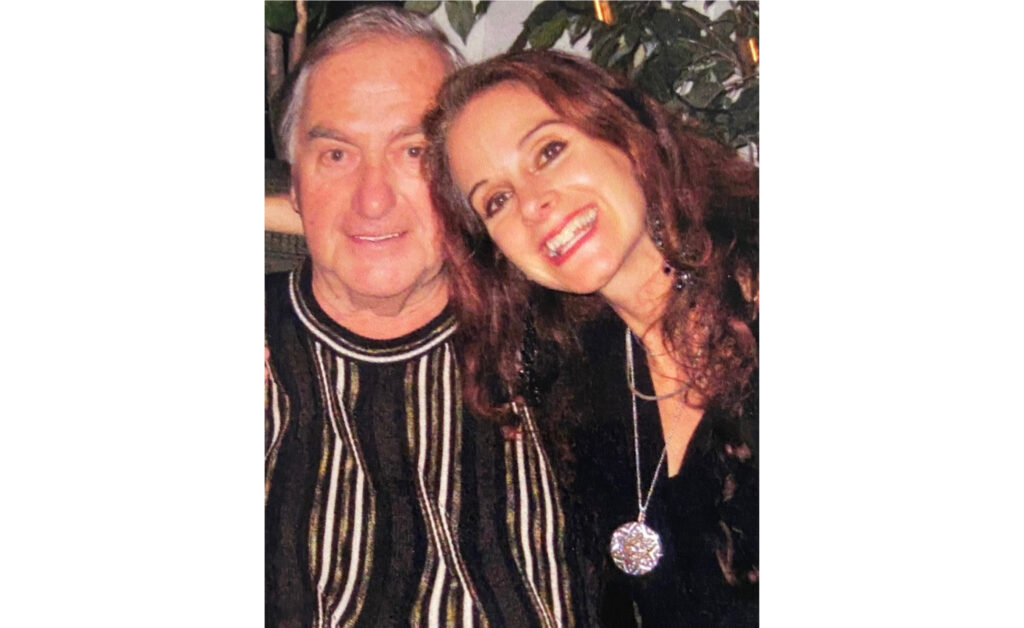

Dad was the quintessential “good guy” – the guy that everybody liked and everybody remembered. He was a kind, gentle man who loved cars, big band/jazz music, Remy Martin, Hungarian cabbage rolls and fine suits. In the last year of his life, those preferences changed to his favourite comfy red blanket, the firelog station on TV and pancakes, pancakes, pancakes.

Dad was my rock, my biggest cheerleader, my confidant and my friend. He would have done anything for his family, and, in recent years, when his physical health and his mind began to fail, we were finally able to pay back some of that same unconditional love.

Dad needed assistance with all aspects of daily living. Being able to work from home, I was in a fortuitous position to help my elderly Mother with his care. In the last year of his life, I even lived with him every other week while my Mother rested and recharged at my sister’s house. I’m sure I probably saw and experienced more than perhaps any daughter should have, but I would do it all over again just for a few more days with him.

One day while helping him in the bathroom, my Dad’s eyes suddenly filled with tears. “I’m so sorry for all the trouble I’m causing you,” he said. My heart nearly broke in half. “Oh, Dad …”, I responded. “I’m happy to help you. Remember when I was little, how many years you took care of me? Well, it’s my turn now.” He seemed temporarily satisfied with my response, but I realized then how painfully aware he really was of becoming a burden. Caught up in the mundane acts of his daily care, I had forgotten that my Dad was still a human being deeply affected by the loss of independence, dignity and self-pride that is our natural birthright.

Watching the slow decline of my Dad into a mere shell of his former self was beyond excruciating, and I often wondered if I’d even survive this arduous journey. But I kept reminding myself that when it was finally Dad’s time to go that I would have no regrets, and that the care and comfort that I had given him in his final months and the memories that we’d shared would sustain me.

Although I had tried so hard to prepare myself for his passing, it didn’t seem to hurt any less. And, months later, the knowledge that he’s truly gone still takes my breath away and aches to my very core.

Then, of course, there’s the inevitable guilt: guilt about the times that I’d snapped at him, exhausted and at the end of my patience; the times that I tried to force him to eat, terrified that he was giving up; and the times that I made him go for a walk when I knew he was tired and shaky.

I try to remember instead that because of my care, he was able to die at home, in surroundings that were comfortable and familiar, instinctively knowing that those who loved him most were nearby. I try to remember that I told him I loved him every night before bed, while wondering if he’d live to see another day. And I try to remember not to beat myself up – that I did the very best that I could under the circumstances, and that Dad knew that.

Most importantly, I try to remember that our unbearable grief is for ourselves, rather than for our loved ones. I intuitively know that my Dad is in a good place; a place of love and beauty, a place with no pain, no anxiety and no fear. While it seems cruel and unfair to take him from us, it’s time for him to move on to the next phase of his soul’s journey. While our loved ones make an indelible mark upon us, their journey is their journey, and we must give them the grace to move on.

And so, Dad, although our hearts are hurting, we know that you’re “up there” with your brother George and your sister Val in Heaven’s kitchen making Hungarian lecsó and listening to some really cool jazz.