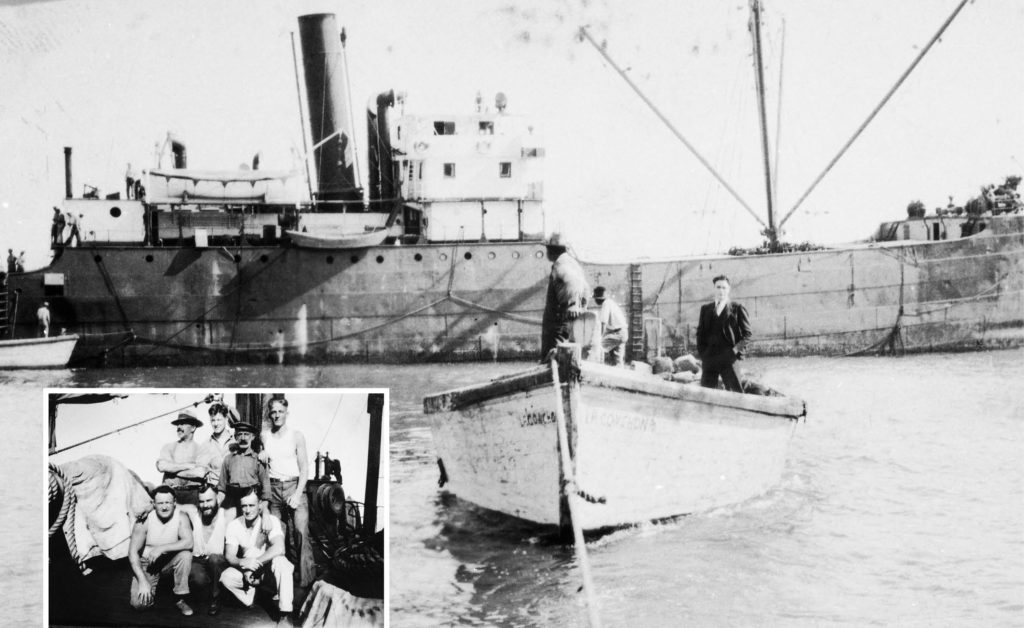

by Doreen Marion Gee | photos courtesy Bill Singer

On a dark day in September, 1924, while en route to Sidney Island on the Beryl G, a liquor smuggler and his son were savagely killed by three American thugs who stole their cache. Fortunately, these violent outbursts were atypical in the rum runners’ heyday, despite the Hollywood hype. Most players were just doing business as usual in a very prosperous market. The tales of the rum runners are a fascinating piece of maritime history, especially since many of their activities happened around the Saanich Peninsula and Gulf Islands.

In his 2018 book – Don’t Never Tell Nobody Nothin’ No How: The Real Story of West Coast Rum Running – Rick James shares: “Probably the most surprising revelation that occurred while researching this book was that, contrary to what most of us have been led to believe, not all smuggling during the Prohibition years was marked by violence.” His book intends to shelve the “hardened criminals” myth surrounding the rum runners.

On January 17, 1920, Prohibition became official in the United States, the same year that B.C. rejected it as a failed experiment. It happened at the worst of times: a severe economic depression following the first world war. Jobless ex-soldiers and their families were desperate for any means to survive and “some soon proved cleverer than others, especially those who happened to own anything that could float.”

The American “Noble Experiment” offered a rare opportunity to make a fast buck from dry throats south of the border: “Rum running (smuggling liquor by water) quickly developed into an extremely lucrative enterprise throughout southern British Columbia.” Rum runners used anything from old fishing boats to large ocean-going steamers, filling their holds with liquor from Canadian distilleries and breweries. From individual entrepreneurs to the big export houses, the rum runners took advantage of southern British Columbia’s prime location for ocean-based commerce. With an archipelago of islands peppered throughout Georgia and Haro Straits plus the close proximity of Vancouver and Victoria to the American San Juan Islands, “the area soon proved a veritable floating liquor marketplace where Canadian boats delivered up orders to their American counterparts in relative safety.”

Sidney’s Bill Singer named his family-owned eatery “Rumrunner Pub and Restaurant”, because their legacy was “a big part of local history.” He met some former rum runners, such as the notorious Johnny Schnarr, who completed 400 ‘runs’ in his career. Schnarr told Bill that a policeman was once heard bragging about arresting him. So, Schnarr brazenly walked into his office and said, “I hear you are looking to bring me in!” He left, a free man.

Canadian rum runners were not breaking any laws as long as they stayed on their side of the border. Any rare incidents of violence were usually by hijackers. “Most B.C. boat operators who took up rum running considered themselves just ordinary businessmen who were providing a delivery service by passing over their cargoes to American vessels well within Canadian waters.” The spirits were hidden away in coves throughout the islands of Haro Strait, including Sidney, D’Arcy, Saturna and Gooch Islands, until the exchanges were made. “Numerous Canadian boats … were working for the big liquor exporters and delivering up their cargo to American boats … An enterprising boat owner could easily make five or six trips a month and collect a profit of $1,000 ($14,000 today).”

However, much larger windfalls farther south lured some daring local rum runners into risking their lives in taboo U.S. waters, usually under the cover of darkness. Their high adventures at sea were the stuff of legends. The rewards were huge: the greater the risks and danger to themselves in transporting the liquor to the U.S. continent, the more they could charge for their product. In Seattle, a quart of good Scotch sold for $3.50 before Prohibition but Americans paid $25 to rum runners for the same spirits during the national crackdown on booze.

Adrian Bogdan, MAS, Assistant Director & Archivist for the Sidney Museum & Archives, adds his expertise: “It is interesting to think about how the manufacture, sale and transportation of alcohol was forbidden across the border, but the Canadian Government was fine with allowing the shipping of alcohol to the States from this side of the border. The Canadian Government was unsympathetic to American pleas for help with enforcing prohibition (assuming they paid Canadian tax on any alcohol being manufactured here!), offering no resistance to Canadians taking their alcohol across the border. This was until the infamous Beryl G incident … and in 1930, parliament finally outlawed exporting alcohol to the United States.”

An exhilarating era had ended, but not the legends or the stories.